Non-fiction

Artists

|

Giovanni Bellini |

Lives of Giovanni Bellini

Edited and introduced by Davide

Gasparotto 2018

This palm-sized book might

be mistaken for a gift book, or stocking-filler, but it's much

more substantial and readable than that. It collects the entries

by Vasari and Ridolfi in each's books of artist's lives, one

written decades after Bellini's death; the other more than a

century later, and very reliant on Vasari, even duplicating some

of his errors. There is also Boschini's verse homage to Bellini,

mostly dealing with the San Giobbe altarpiece, and the famous

correspondence between Isabella d'Este and her representatives

and Bellini himself. These latter letters are often mentioned

but it's entertaining to read them, and track Isabella's

mounting impatience with Bellini ever producing the painting

she's paid a deposit for. Eventually he agrees to paint a

Nativity, but then she says she wants it to include John

the Baptist! And at one point she excuses herself from providing

the measurements for the space a painting is to fill by saying

she couldn't stay in Mantua long enough to measure up because

the plague had broken out. Good excuse! The Vasari and Boschini

excerpts are the meat of the book, though, made even more

valuable by the notes detailing errors and the present

whereabouts of works mentioned. An essential little treat for

Venetian art buffs and Bellini fans. duplicating some

of his errors. There is also Boschini's verse homage to Bellini,

mostly dealing with the San Giobbe altarpiece, and the famous

correspondence between Isabella d'Este and her representatives

and Bellini himself. These latter letters are often mentioned

but it's entertaining to read them, and track Isabella's

mounting impatience with Bellini ever producing the painting

she's paid a deposit for. Eventually he agrees to paint a

Nativity, but then she says she wants it to include John

the Baptist! And at one point she excuses herself from providing

the measurements for the space a painting is to fill by saying

she couldn't stay in Mantua long enough to measure up because

the plague had broken out. Good excuse! The Vasari and Boschini

excerpts are the meat of the book, though, made even more

valuable by the notes detailing errors and the present

whereabouts of works mentioned. An essential little treat for

Venetian art buffs and Bellini fans.

Johannes Grave

Giovanni Bellini: The Art of

Contemplation 2018

In vast contrast to the above, this one

is a challenge to the muscles in the average lap - it's huge. This is good for

nice big illustrations and telling details, but not so good for

reading comfortably. So I haven't yet, but when I do you'll be

the first to know. The book's angle is the appreciation of how

Bellini's works are all about contemplation and meditation,

rather than excitement and narrative. As someone who has spent

untold time doing just that in San Zaccaria and the Frari, I

find this perspective compelling, and always have. |

|

Daniel Wallace Maze

Young Bellini

2021

Bellini's parentage and date of birth

have long been sources of disagreement and conjecture amongst

scholars. The author of this book attempts to settle the issue

by gobsmackingly asserting that Giovanni is Jacopo's half-brother,

not his son. That Jacopo was much older than Giovanni is used to

explain their being viewed and described as father and son,

because Jacopo was like a father to his younger brother.

Accepting this allows Giovanni's birth to be earlier and his

career to shift forward enough years to ascribe various

unsophisticated studio-of-Jacopo works to him (and the

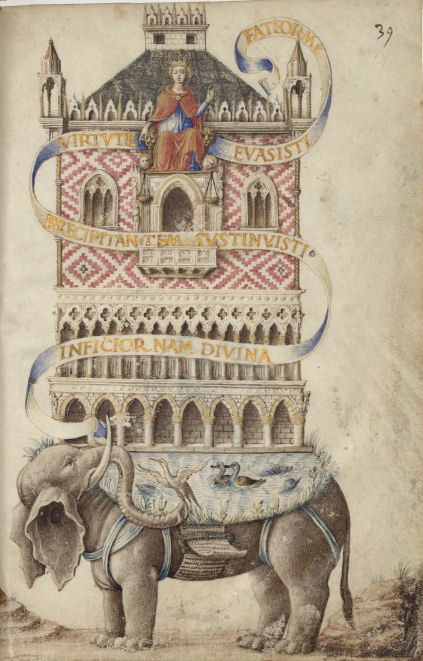

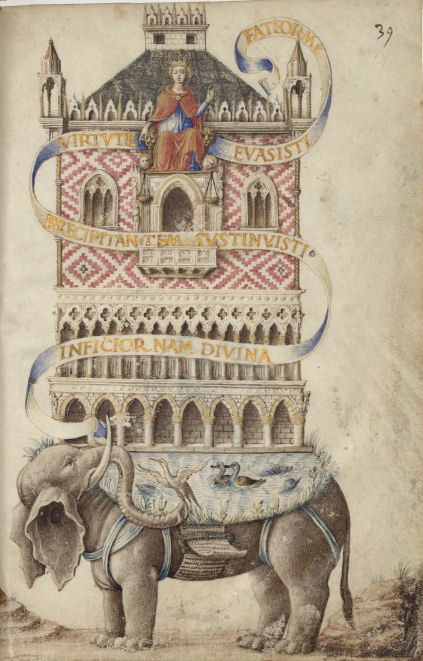

illustrations in the Life and Passion of St. Maurice,

previously given to Jacopo or Mantegna, see below) and to

give him the advantage in the arguments about which way the

inspiration flowed between him and Mantegna, his brother in law.

These major shifts

in scholarship are not unusual, but this is the first one to so seismically shift

our understanding since I've been studying closely enough to be

knocked sideways. It's certainly not a theory to be dismissed

easily, and may gain traction. Meanwhile this is a readable and attractive book,

well-illustrated and clearly argued. I liked the observations of the

influence of Altichiero upon young Bellini, as he's another

favourite of mine, but could have done without the

typically-American need for every artist and work to be described

with a superlative. The story ends just as Giovanni gets good,

because at that stage the author's theories become less

important. The book has two appendices setting out his

discoveries and assertions, one of which is the debunking of the

old assertion that there must have been another member of the

family also called Giovanni. He admits that Bellini scholarship

has hardly taken his theory to their bosoms, but that claims

this book tightens up the argument somewhat. We shall

see.

not unusual, but this is the first one to so seismically shift

our understanding since I've been studying closely enough to be

knocked sideways. It's certainly not a theory to be dismissed

easily, and may gain traction. Meanwhile this is a readable and attractive book,

well-illustrated and clearly argued. I liked the observations of the

influence of Altichiero upon young Bellini, as he's another

favourite of mine, but could have done without the

typically-American need for every artist and work to be described

with a superlative. The story ends just as Giovanni gets good,

because at that stage the author's theories become less

important. The book has two appendices setting out his

discoveries and assertions, one of which is the debunking of the

old assertion that there must have been another member of the

family also called Giovanni. He admits that Bellini scholarship

has hardly taken his theory to their bosoms, but that claims

this book tightens up the argument somewhat. We shall

see.

|

|

Carpaccio |

Jan

Morris Ciao,

Carpaccio!

This small book has the appearance of a 'gift

book' and was published just before Christmas 2014. But to put it in this

category (and hence by the lavatory) is unfair. It is dominated by

illustrations, true, and the text isn't exactly one of art-historical

rigour, but it is a book which definitely Carpaccio fans and probably Venice-o-philes

will want to own and read. The author admits to not being an art historian

and her approach is to react, as a clued-up person admittedly, to the

paintings' content and imagery directly, with no agenda beyond enjoyment. This would usually be a part of a fuller appreciation of an

artist's work, influences and technique but it also works on it's own,

providing insights and pointers to bits you might have missed and generally

freshening up your view of a painter who can come across as a little dry,

and overshadowed by the likes of Titian and Giorgione, but doesn't here. In an overlap with the book above animals and birds do

dominate, as I suppose they must for the painter of a famous winged lion and

many famous dogs and horses, but there's also an interesting chapter where

the Life of the Virgin sequence that he never actually painted but

here is

created from the paintings of her life which he did separately. His careful

and authentic representations of boats get a later chapter, as does his fanciful

yet convincing architecture, which is fruitful as it reflects the mix of fantasy

and reality that characterises his work. The illustrations, especially of

details, are carefully chosen and positioned so that references in the text can

be inspected without explicit directions or page-flipping. Nifty. Which all goes

to make this little book a rather necessary purchase. and was published just before Christmas 2014. But to put it in this

category (and hence by the lavatory) is unfair. It is dominated by

illustrations, true, and the text isn't exactly one of art-historical

rigour, but it is a book which definitely Carpaccio fans and probably Venice-o-philes

will want to own and read. The author admits to not being an art historian

and her approach is to react, as a clued-up person admittedly, to the

paintings' content and imagery directly, with no agenda beyond enjoyment. This would usually be a part of a fuller appreciation of an

artist's work, influences and technique but it also works on it's own,

providing insights and pointers to bits you might have missed and generally

freshening up your view of a painter who can come across as a little dry,

and overshadowed by the likes of Titian and Giorgione, but doesn't here. In an overlap with the book above animals and birds do

dominate, as I suppose they must for the painter of a famous winged lion and

many famous dogs and horses, but there's also an interesting chapter where

the Life of the Virgin sequence that he never actually painted but

here is

created from the paintings of her life which he did separately. His careful

and authentic representations of boats get a later chapter, as does his fanciful

yet convincing architecture, which is fruitful as it reflects the mix of fantasy

and reality that characterises his work. The illustrations, especially of

details, are carefully chosen and positioned so that references in the text can

be inspected without explicit directions or page-flipping. Nifty. Which all goes

to make this little book a rather necessary purchase.

Carpaccio in

Venice: a guide edited by Gabriele Matino and Patricia

Fortuni Brown 2020

As the big Carpaccio show

in the Doge's Palace has been postponed from 2020 to 2023 and

Peter Humfrey's new book about the artist with it, this book

will have to do for a while, scholarship-updating wise. And it

does a good job. It provided a fair few revisions of entries on

Churches of Venice, mostly for the scuole, often with

regard to changes in attribution, mostly after restoration work.

Needless to say the expensive restoration work has resulted in a

solid upgrade in all cases. The book has lots of nice photos,

and details, needless to say, and a stylish layout. Having the

sites arranged by sestiere seems logical but results in, for

example, the scuola building dedicated to Saint Ursula and

the art from it in separate chapters and 40 pages apart. But I

nitpick - this is as good as it gets in helping you find

Carpaccio's works and traces in Venice, and telling you all

about what you're looking at. Save Venice was involved in the

publication so you have to put up with the bigging-up of their

restoration work and the listing of the rich Americans who

provided the funds, and to whom the phrase 'no, I prefer to

remain anonymous' does not come, naturally. Is it a tax thing?

|

|

Giorgione |

|

Enrico Maria Dal

Pozzolo Giorgione

Attentive readers of my sites

might be surprised by how few books about artists there are hereabouts.

It's not that I don't buy them, it's just that most are bought for the

illustrations and usually have disappointing text, often losing fatally

much in the translation. But here we have a lush and lovely book with

fascinating and elegant text, and so I thought I'd share. The language

sometimes slips into eccentricity, it must be said, with the frequent use

of the word 'terse' to describe landscape a noticeable oddity. This is not

the first time I've noted this word used wrongly/oddly in books translated

from the Italian. Maybe it's a mistranslation of a word that might more

comprehensibly be rendered as 'stark' say, or 'sparse'. There is

laughably little known about Giorgione, and the author fesses up to this

hindrance from the off, with a chapter dealing with the certainties. One painting is signed (but on a slip of paper

stuck to the back) and the artist's contested payment for his (largely

lost) work on the frescoes on the outside of the Fondaco dei Tedeschi is

documented. Apart from the notes of a connoisseur who visited palazzi in

the 16th Century and Vasari, with whom pinches of salt ever need to be

taken, that's all the documentation. The action of reading between lines

and following trails is the fascination here, and the book spins

convincing conclusions whilst avoiding tempting wild assumptions. The

second chapter, on the art world and wider society while Giorgione lived and

traded, is enlightening too. Then we get to the third part, and the meat of

the book - each of Giorgione's works, the contested and the confirmed,

dealt with in fine detail and many fine illustrations. The first work is an

impressively enigmatic work in the Tempest vein which I had not seen

before, Pozzolo calls it Saturn Exiled. Looking to the caption I see it belongs to the National Gallery in

London! Now the rooms of the NG are as familiar to me as the rooms

in my own house, but it seems this lovely puzzling painting is rarely

displayed, its showing dependant on whether current art-historical opinion

is ascribing it to Giorgione or not. Shame.

Update: The painting, which the NG calls Homage

to a Poet by a 'follower of Giorgione' is in Room A, down in

the basement, which is open Wednesday afternoons only, 2.00-5.30. I went on a Wednesday afternoon to check it out and, well, it's

a sweet painting and in a good state of preservation, but if

that's a Giorgione then I'm a gelato. The faces look all wrong. Room A is

a big scruffy hangar, but there's some interesting stuff. Mostly 'attrib's

and 'follower of's, but some surprises, including a Carpaccio in a very

poor

state.

|

|

|

|

Tintoretto |

|

|

|

Lives of Tintoretto

(Partly) translated and edited by Carlo Corsato

Like the Lives of

Bellini and Veronese in the same series, also reviewed around here, this book is

more comprehensive, enlightening and entertaining than you might expect from

something so small. (Insert jokes about my, and indeed Tintoretto's, physical

stature.) The quality of the illustrations is again high, in every way, but it

is thicker than the other two. After Corsato's helpful intro there's Vasari

first, of course, and he's dismissive, of course, as Tintoretto isn't a

Florentine, accusing him of being slapdash and rushing his work. But here

Vasari's shortcomings are also pointed out by El Greco, courtesy of annotations

he added to his own copy of Vasari's Lives. We then get brief chapters with

letters to Tintoretto. Firstly from Pietro Aretino, thanking the artist

fulsomely for the paintings on his ceiling.

Andrea Calmo, an actor and playwright who helped

Tintoretto to many early commissions, including Aretino's, is even more florid

in his praise, describing him as a peppercorn and kinsman of the Muses who

'should be glad that, young as you are, you have been endowed with great verve,

a light beard, a profound intellect, a small body but great spirit'.

Veronica Franco uses more sober language, but is obviously very smitten with her

portrait. But the meat of this book - around three quarters of it - is the 1648

Life by Carlo Ridolfi. |

|

The Tintoretto 2019

500th birthday book and exhibition glut

As an admirer but not a lover I didn't indulge

much, but the From Titian to Rubens exhibition was visited,

and the two catalogues and two books were bought. They all relate to

the content needs of

The Churches of Venice, you see,

and mostly have a strongly Venetian air of deception about them.

|

From Titian to Rubens

- Masterpieces from Flemish Collections MUVE

The exhibition, at the Doge's Palace, explored the connections

between Venice and Antwerp around the time of Rubens. The connections

varied in weakness - the Rubens works had little connection to Venice and

the highlight Titian was unconnected to Antwerp, for instance. But the

exhibition undoubtedly had its fascinations. The draw for me, though, was

the Tintoretto from the demolished church of San Geminiano, bought by

David Bowie and sold at his death to a private

collector who's now given it to the Rubens House in

Antwerp, from where it's to be on

long term loan here. But this book, as well

as

the catalogue-content proper, has

essays on art in Antwerp, the use of Venetian

glass

in Flemish still-life paintings,

harpsichords

and books, but nothing about the Tintoretto. For that you needed to buy... as

the catalogue-content proper, has

essays on art in Antwerp, the use of Venetian

glass

in Flemish still-life paintings,

harpsichords

and books, but nothing about the Tintoretto. For that you needed to buy...

David Bowie's Tintoretto: The

lost Church of San Geminiano MUVE

Published to coincide with the 2019 exhibition From Titian

to Rubens - Masterpieces from Flemish Collections in the Doge's

Palace, this is a revised and redesigned version of a book about the

painting published by Colnaghi in 2017. The crowd-pleasing title is

somewhat deceptive. There is an essay on the church, but it also contains

longer pieces on the painting itself, its restoration, and on the

connections between Venice and Flemish artists, like Rubens, van Dyke and

Maerten de Vos - subjects germane to the exhibition but not really

suggested by the book's title. A short piece recalls relevant bits of

David Bowie interviews. This variety means that it serves more as the

second volume of the exhibition's catalogue than a book about Tintoretto

or the church.

|

|

Floriano Boaga

Discovering Tintoretto in the Venetian Churches Editoriale Programma 2018

Well here's an odd one. It's colourful, glossy and inexpensive but, despite the

title, it's actually a book of walks in Venice, arranged by sestiere,

with a short paragraph or two about a particular church beginning each walk. The

Tintoretto works in that church get usefully illustrated with a photo and a

paragraph, admittedly, so it's more a book of walks than art history, also

taking in the churches that don't contain works by Tintoretto. Still, a handy

little bargain, and the occasional translation glitches are all part of the fun! As

are the sarky mentions of Napoleon - never by name, and with ironic quotes

around words like

great

and liberator.Looking at Tintoretto with John

Ruskin

Compiled and edited by Emma Sdengo

Marsilio/Scuola Grande di San Rocco 2018

A book of John Ruskin's writings about Tintoretto, this one is arranged

alphabetically by building - churches mostly. San Rocco dominates, which is fair

enough as the book is published by them, and the first third of the book is an

essay on Ruskin and San Rocco by the compiler. The alphabetical-ordering is a bit

cranky - Moisè, Church of St is followed by Orto, Church of Santa

Maria dell' for example. Handsomely produced, with copious illustrations and

useful plans, this does its job well for fans of the painter and the writer.

|

|

Titian |

Sheila Hale

Titian: his Life and the Golden Age of Venice

That this book should deal so well with

Titian's career makes it worth your attention, that it also

investigates life and politics and art in Venice as he arrives

and progresses makes it essential. The author initially paints a

vivid picture of the Venice Titian discovered when he arrived

and doesn't scrimp, for example, on giving us the full

background on his first tutors, the Zuccato and Bellini studios.

Later on important friends, patrons and events get discussed

very fully, much more than matters like Titian's technique of

development as an artist, and I for one learnt lots. My

favourite expansion was with regard to the Pesaro Altarpiece in

the Frari church, which I knew had been commissioned by

Jacopo Pesaro,

whose nose had been put out of joint by a hated cousin's

commissioning of Bellini's altarpiece in the same church. But

here I learned that the Pesaro Altarpiece had been commissioned

by Jacopo to commemorate an obscure naval victory - Santa Maura

- during which he had fought for Pope Alexander VI, not Venice,

and months later Santa Maura had been given back to the Turks

anyway as part of a peace settlement. Those few who might've

remembered the battle by the time the altarpiece was installed

would have seen cousin Benedetto, the one who'd commissioned the

wonderful Bellini triptych, as the hero of Santa Maura. It's a

considerable weight of book in paperback, so I decided to go the

e-book route. You thereby lose out on the easy contemplation of

maps and Titian's family tree and the interspersed batches of

colour reproductions of the major works, but on balance these

were sacrifices I was willing to make for ease of reading. And

an easy read it is, and a book which, when you finish it, you

fell you've really read something, and something more than just

an artist's biography.

|

|

Mark Hudson

Titian: The Last Days

Setting out initially to see if he can find traces of Titian's

famously shadowy last canvases, the author also writes about the

artist's life and development. He does this through devoting

chapters to Titian's teachers and pupils and colleagues and

through some present-day travelogue and interviews. The modern

stuff varies from the pointless to the fascinating. Amongst the

latter is a chapter on the Venetian art dealer who's façade as a

dealer in pretty - mostly 18th Century- stuff for tourists masks

his real interest in buying real art by the like of Tintoretto

and Titian, preferably before anyone else notices it quality and

provenance. The tone of the book is winningly, if sometimes

overly, cynical, but informed and discerning. The author's

contempt for art historians is refreshing, if a little splenetic

and his approach is often nicely non-standard. I'm not sure

you'll find another book about Titian where there's so much

conjecture as to whether he shagged his models, for example. An

easy, breezy read that combines well with your dryer (and better

illustrated) books on Titian.

Paolo Veronese |

Diana Gisolfi

Paolo Veronese and the Practice of Painting in Late

Renaissance Venice

Books about Paolo Veronese are not getting

frequently written, and books which begin by devoting a solid

two chapters to his influences and colleagues during his early

years in Verona are even more rare. So that's me won over.

Adding to the positive is the fact that his career and works in

Venice are copiously compared to those of his competitors and

collaborators there, especially Titian and Tintoretto, but also

the latter's sons and Palma Giovane. On the negative side is the

concentration on technique and materials. This aspect adds

texture, for me, but I can have enough of it, and I'll admit to

skipping the paragraphs which list pigments. And the discussions

of how each image was transferred from drawings, and the

discovery of the traces and indentations that tell us so

much...well it's good to have the benefit of new technical

analysis, I admit, but sometimes not exactly exciting. The

catalogue of the 2014 Veronese exhibition at the National

Gallery in London is probably the best recently-published

introduction, and this 2017 book brings matters nicely up to

date and covers the, sometimes unusual, topics I mentioned.

There, you're all grown-ups, I think that you can now decide if

you need this one.

Claudia Caramanna et al

Paintings from Murano by Paolo Veronese

Also in 2017 there was the exhibition at the Accademia of two

paintings that Veronese made for a church on Murano, for which

this book is the catalogue. Well, calling it a catalogue is

maybe an exaggeration. It's smaller than its price might make

you expect, in every dimension, and contains six essays of

various lengths, some two pages long, the longest one twelve.

There are also twelve pages of congratulatory forewords by the

gallery boss, the cultural director of the Venice Curia, the

heads of three charities involved, and the CEO of the sponsors.

It's a shame we didn't get to hear what the manager of the firm

hired to do the catering at the press launch had to say. Add to

this the frequent copy errors in the text and you might think

that this will be a hard book to recommend. Well it does

concentrate on the much-needed restoration, if that's an area of

interest for you, and the essay on the history, commissioning

and movement of the panels is more detailed than anything I've

read elsewhere. (They were painted for

Santa Maria degli Angeli

but ended up in

San Pietro Martire.) But I think that this is a book for

only the most committed of Veronese fans. Not least because the

paintings themselves are a bit dull, and are likely by his

brother and son. |

|

Lives of Veronese

Translated and introduced by

Xavier F. Salomon

Bought in the wake of the

discovery of the Lives of Giovanni Bellini book reviewed

above, this is a similarly academically valuable little book.

Here Vasari's pitifully paltry mentions, found in other artists'

biographies, are followed by an equally sparse entry from

Borghini. These sections each barely stretch to double-figures

of pages, so the 140-odd pages of the biography of the artist by

Carlo Ridolfi are why we're here. It's the first translation

into English of the whole thing and so a very valuable

resource. As it lists and describes Veronese's works

chronologically and in much detail it can sometimes read more

like a resource than a pleasure, in fact - more useful for

reference than for reading. But there's just about enough

digression, poetry and purple prose to keep one reading, with

some judicious skipping advisable when the descriptions get a

bit dutiful. It has judiciously chosen and gorgeous

illustrations too, well positioned near the text, and notes as

to the current whereabouts of the works, like the Bellini book.

The Bellini book is more entertaining and readable, but this

one's useful too. |

History, people and buildings

A 2018 observation - odd how the alphabet

has grouped together, over the years,

four unusually snarky books and/or reviews amongst the first five.

|

Peter

Ackroyd

Venice: Pure City

Coming as is does with an attached TV series, you'd be

forgiven for thinking that Peter Ackroyd is here merely 'doing a Da Mosto'

and starting to read the book does little to stifle these cynical suspicions. Ackroyd's similar, though much larger, book about London is a well-reputed

recent attempt at summing up a whole city, its history, people and

character, using a chronology-mangling and artfully random chapter structure. It

worked for London (although not for me) but here it results in more of the

same for readers of the already very many books about Venice. After a brief intro dealing

with the foundation the chapters do the usual stuff with topics like stone, art,

water, trade, myth-making, sex, hubris and decay. It's

all done very readably, much more readably than usual in Ackroyd's

non-fiction in fact, which often tends towards somewhat self-conscious

flights of style. And if you've never read a history of Venice, or any of

the variously formatted meditations on its unique features (of which a fair

few are reviewed on this page) you might learn much here. A chapter on nature in Venice, its lack and its

incursions, makes fresh reading, but then when talking of the smuggling in

of nature in the grain and fossils within its stones and pillars Ackroyd

fails to mention San Giacomo dell’Orio - a rather glaring oversight, this

church being fossil-flecked-column central. Maybe his research assistants,

credited prominently in the acknowledgements along with only his editors,

didn't venture that far out. He quotes from two sources new to me, aside

from the usuals like Sanudo and

Coryate. One of these is one James Howell,

who has the same surname as my Mum, so maybe I'd better get family-tree

checking. The book's central thesis is that Venice is a prison and that

Venetians have ever been docile and more inclined to be part of a larger

whole than individuals. This allows him then to posit the convents and the

Ghetto as Venices in miniature. I'm not entirely convinced myself. A readable

400 pages, I suppose, but disappointingly unspecial.

|

|

|

Louis Begley & Anka Muhlstein

Venice for Lovers

A bit of a librarianly quandary with this one.

It is made up of three parts - one short story, one piece of travel writing

and one piece of lit-crit. So, should it go with the fiction or here? Well

I've gone with the librarians who catalogued the copy I've just read. Mr

Begley wrote Mistler's Exit - a novel I

didn't like, and here he turns in a short story again full of the self-love

and admiration for rich people that turned me off then. But these themes take a back seat here to

some pretty overt wish-fulfilment erotica. The primary early lust-object is

again a college-days sweetheart, who spurns our hero, despite the influence

of Venice, and later becomes more than a bit of tart. Lovely. The second

part, by Begley's wife, is about the restaurants that the couple have become

recognised regulars at. It's more about people than food, and is the best

part of this book. In the third piece Begley looks at how great authors have

used Venice, with lots of big quotes and plot spoilers. His examples are

Henry James, Marcel Proust, Thomas Mann and, of course, himself. My case rests.

Anna Bellani The Venetian Safari

I must begin by telling you that I am not a

child, and as such I am not the intended audience for this book. It consists

of four walks in search of sculpted animals - one walk each for the sestiere

of Castello, San Marco and Cannaregio and a fourth taking in the other

three, called De Là de L'Acqua ('across the water', as the Venetians have

it). The walks are in large print with nice big photos, but small amounts of

background knowledge. There's no explanation of why a house might have a

giant bee on it, or why a pair of turban-wearing brothers are there but, as

I say, I am a grown-up and like to learn stuff. For a small child following

and finding this is an ideal first step, and should help make fascinating a

city which is not the most child-friendly. And I confess that I am tempted

to do the walks as the animals carved and photographed do look worth

finding, especially the pair of cats in Dorsoduro (see photo above)

although visiting when the trees have no leaves is advised for this one.

|

|

John Berendt

City of Falling Angels

When this was published in 2005 reviewers tended to

dismiss it as muck-racking and gossipy froth. The book mostly concerns

itself with the devastating fire at the Fenice opera house, and the

subsequent investigation and typical Italian flurries of accusation and

innuendo. The other major strand concerns Jane Turner Rylands, who Bernedt

accuses of being a scheming necrophile in general, and an embezzler of

Olga Rudge in particular. The controversy over Rylands attempting to get the Ezra

Pound letters and papers out of Rudge, Pound's mistress,

for a song is explored in much detail. Rylands (the wife of the director of the Guggenheim) subsequently exacted

some small revenge when she published her second book of Venice-set short

stories, called Across the Bridge of Sighs.

One of the stories

features an unscrupulous American journalist called Cad Peacock who gets

his eye spat in, and the stories evidently contain more thinly-veiled

unfavourable portraits of people who condemned her over the Pound

business. Aside from these two attention grabbers there are portraits of

people - important and eccentric - who live, move, and shake in Venice

today and, I think, it provides a useful update to all the books about

Venice as it was. When I read about and admire, say, Palazzo Barbaro I

sometimes wonder how it's surviving into our Century, and this book tells

you. You'll also learn about pigeons, rats, Woody Allen and the wear and

tear caused by film crews in fragile palazzos. I'll admit, though, that when

I got to the bit about the restoration of the Miracoli church and the

bickerings within Save Venice I started to more fully appreciate the

criticisms that, in the face of the beauty of Venice, to

concentrate on

the festerings underneath is a perverse choice. I skipped much of this

section as it was contributing very little to both my understanding of

Venice and my will to live. A mostly very readable book about

Venice for our times, then, with all the benefits and disappointments that

that implies.

Bidisha

Venetian Masters Under the skin of the City of Love

OK, the problems first. Number one: what's with her not having a

surname? She's not Kylie, or Prince. Secondly, why is the cover so bad? A

drawing of generic, but not authentic, Venetian-type domes. Getting beyond

these minor trials one is immersed in the life of a young woman who decides to go

and live in Venice for a few months in 2004. She has a rich friend, who has very rich

parents who live in a Grand Canal-side palazzo. She meets people, makes

friends, eats

meals and ice cream, and learns about the locals. She writes well and

sharply about the people, and makes a very good go at the city itself and

its buildings. (I'd never thought that the Frari church looked like Bourbon

biscuits myself, but I'll have a compare next time I'm there.) There's very

little actual art appreciation as such, which makes the title a bit

confusing. (She also makes the daft mistake of mixing up the (small)

Bellini altarpiece in the Frari with the (huge) Titian one.) Maybe it's to

do with getting a symbolic masters degree in being Venetian? Dunno. The fact of our observer being more at home in

bars and social gatherings, rather than art galleries and churches, is

sometimes over-apparent - this is a book more full of evenings than

daytimes. And the unrestrained pointedness of her evaluations of a lot

of the people she meets makes you wonder at their reactions, and the warmth

of her welcome back. She is also refreshingly unflinching in her portrayal

of the misogyny and prejudice she encounters. This all gets more than a

little out of hand, though, in the final section - a later visit for the

Biennale - where her feminist rhetoric, hyper-sensitivity to perceived

slights and bitchiness towards her friend's mother begins to leave

a bad taste in the mouth. She has a rant about the only famous Venetian

women being 'colourful poetry-spouting hookers' and the like, and how women

artists were 'locked out'. She thereby fails to give any credit to Marietta

Tintoretto and Rosalba Carriera, two admittedly rare exceptions, but no less

worthy of mention and praise for that. If you can get beyond the

bile, the book can be a perceptive and flavoursome

Venice fix from a different perspective than usual. Or it might just make

you flinch too much for real enjoyment.

|

|

Giacomo

Casanova

History of my life

translated

by Willard R. Trask

Johns Hopkins 1966-71

He's Venice's most famous son, and

one of those rare people whose name has entered the language - everyone

knows what he liked doing, and so anyone with an enthusiastic but light-hearted attitude

to love is likely to get called a Casanova. This is not entirely

unfair, but it's also not the whole story. He saw himself as a man who

loved well and often, rather than one who trifled with women, and it's a view you

can have some sympathy with. He writes so well, feelingly, and

perceptively about society in 18th century Europe that you can't help

admiring him. His story starts with his childhood in Venice and he returns

home at intervals from

his travels around Italy and Europe. And his adventures are sufficiently varied

and spicy to hold your attention like a good novel of the period would.

This translation, published in paperback in six handsome double volumes, was

the first untamed edition.

|

|

|

|

|

Thomas Coryate

Most Glorious & Peerless Venice

(edited by David Whittaker)

If you've read much about Venice's later history then Coryate's name

will have arisen. His 1608 book Coryate's Crudities is frequently

mentioned as a primary source on life (specifically the experiences of a

visitor) in Venice in the 17th century. But how many of us have read the

book itself? Not me, I admit. So, praise be to David Whitaker who has

collected the Venetian section of the Crudities into one

handsome paperback and in the process made the language more comprehensible,

without losing its quirk and charm, I think. It's not the most concise and useful of

guides, but it has flavour and eccentricity to make amends. This is not a

book to read to learn, as such, but I did learn that the classic six-pronged

gondola prow didn't appear until around 1630; and that Colleoni, of the

equestrian statue, was so called because he had three testicles, coglioni

being Italian slang for a testicle. There's also a discussion of why

there were no horses in Venice, which has been a contentious topic in a

couple of conversations I've had with Venice buffs, it having been argued

that there were, which is madness. And Coryate loves his numbers, boy does he

love his numbers! If you've ever wondered how many paces it takes to cross

Piazza San Marco, or how many steps are on the Rialto Bridge, then Coryate

is your man. Another eccentricity is how, even when visiting the Scuola di

San Rocco, he never mentions the names of artists. He rhapsodises about the

music he hears here too, but similarly doesn't mention any composers.

Although he does tell us that the musicians who performed in the Scuola were

paid a hundred ducats, which he tells us is equivalent twenty-three pounds

six shillings and eight pence. He also experiences a Greek Orthodox service in San Giorgio and

discusses the Jewish religion. He seems to find Jews to be strangely like

other human beings, but still thinks that their religion is an abomination.

Courtesans and the divers varieties of melons on sale get a fair amount of

coverage too, the former with unconvincing apologies and disapproval, the

latter with warnings of

the danger of death if you eat too many. All good eccentric stuff, and

genuinely and fragrantly evocative of its time. |

|

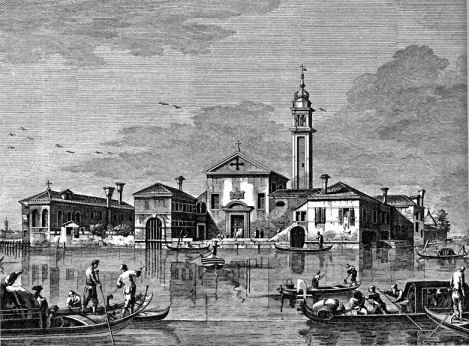

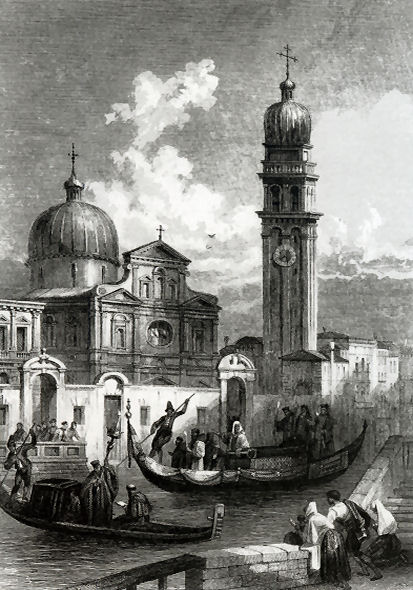

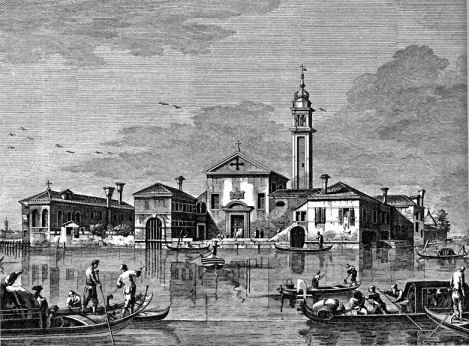

Giorgio & Maurizio Crovato

The Abandoned Islands of the Venetian Lagoon

(Le isole abbandonate della laguna veneziana)

This book was originally published in 1978

by two journalist brothers who were shocked and ashamed at the

way the history and treasures of the Venetian lagoon islands had

been ignored and plundered for so long. The original book, which

followed an exhibition, documents the islands' sad decline and

dilapidated state. This updated edition provides some cause for

optimism that the situation has changed much in the intervening

years. The brothers undoubtedly did good, though, raising

awareness and also reawakening interest in the use of

traditional rowing skills, which had been long in decline and

are now again flourishing, what with all the anti-motorboat

feeling and the increasing knowledge of the damage they do. The

new edition of the book (which has Italian/English dual text)

has an updating introduction by the brothers and then a chapter each on thirteen of the islands, consisting of

historical texts describing the island in its glory days, then

some lovely old prints made back in them days (there's one

below) and photos of

their sad 70s state (that's one on the right). These black and white photographs

(which are also the work of the brothers) are a

major part of the pleasure of this book, at least for this fan

of romantic ruin and crumble. The future is looking less bleak

for some of the islands as they are being preserved and converted to uses

ranging from luxury hotels to a

museum of lagoon history and facilities for various educational

institutions. All these efforts deserve our support and 10% of

sales of this book in the UK will go to Venice in Peril, and 10%

of US proceeds will go to Save Venice. So the least that you can do

is buy and enjoy this book. You can get it from the publishers

sanmarcopress.com,

some shops in London, most of the bookshops in Venice and many online sources. |

|

|

|

|

|

Andrea di Robilant

A Venetian affair

In the attic of the family's palazzo in Venice the author's father finds a box

of letters made into damp wads by time and humidity. These turn out to be

further evidence of the torrid relationship between Andrea Memmo, an ancestor,

and a half-English woman called Giustiniana Wynne. Using these and other letters

Andrea di Robilant pieces together a story of brazen love, and romance thwarted,

in 18th century Venice. The story of the affair is interesting enough, but the

book also evokes the era well - the time of Venice's fading as a real power and evolving

into a magnet for visitors. Hitherto Venice would be known more for its visitors

than its natives (see John Julius Norwich's Paradise of Cities - reviewed

below) and so it's appropriate that Consul Smith and

Casanova play their parts here, as an early influential foreigner and the last

famous native respectively. The love story evolves at a stately pace but has

just enough events and details, sometimes lovely sordid ones, to keep you

reading. Just as mobile phones are essential to the development of any affair

nowadays, so masks where a big help back then. As Giustiniana is banished back

to England, via Paris, so the tale takes on a sadder note as the making of

choices and the wasting of lives becomes the theme, and our heroine evolves

into a far stronger and more ambiguous character. The emotions are well

observed and identified by the author, who fills in gaps in a convincing

way, and so you end up with a strong feeling of real lives.

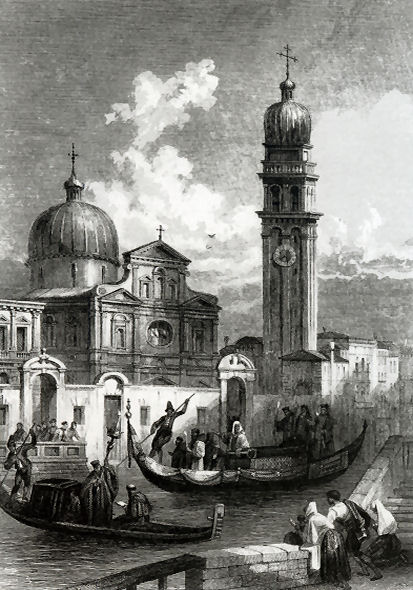

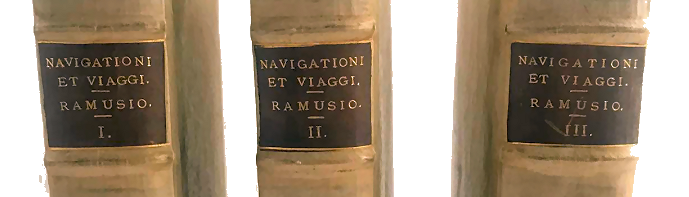

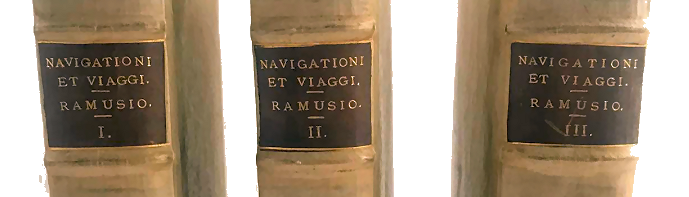

This Earthly Globe - a

Venetian Geographer and the Quest to Map the World

The author is on more serious ground here, and covers

more ground, like The Whole World! The book is about Giovambattista Ramusio

who worked for the Venetian government during the time when the world was

becoming a much bigger place, but knowledge was guarded by the countries

doing the discovering. Ramusio travelled a bit but also gathered a lot of

the reports and diaries of others, a task made easier by his diplomatic

connections. His collection resulted in Navigationi et Viaggi, a

multi-volume book, published in 1550-59, and invaluable ever since. These

reports take up most of the book, and are fascinating, so this is not so

much a book about Venice. But there is a goodly amount of writing about

famed printer Aldus Manutius, a constant colleague of Ramusio, so the

Venetian flavour remains strong. |

| |

|

|

Iain Fenlon Piazza San Marco

If, like me, you look upon the Piazza San Marco

as a crowd-infested nuisance to be passed through as quickly as possible

then you, like me, may be in need of something to reawaken your fascination

for what is arguably Venice's most important space. This book could be that

something. The writing is much more elegant than we have any right to

expect, the stories are well told, and the scepticism at the more

far-fetched of these tales is refreshing. After a very interest-stirring

introduction the chapters begin with the myths and early history of the

Piazza and Venice. The fascinating conjecture here for me was how, having

been founded well after the Roman Empire, Venice lacked the status that such

ancient history conferred, and so the mythologically loaded story of St Mark

and his vision, and his remains being brought to Venice, conferred some much

needed theological clout and state-cred. We're then taken through the

history of the piazza up until the present (tourist-infested) day. The

chapters are themed with, for example, a chapter on the processions and

rituals (including fascinating details of the doges' funerals) which is followed

by one devoted to the traders, performers and scammers who have always been

a fixture. Everything from the most important political events to ritual pig

disembowelments and a Pink Floyd concert have happened here, with the

performance of rituals and music and problems with traders and

visitors being pretty much constant themes down the centuries. The last

chapter ends with the observation that the problems facing Venice today are

to be seen concentrated into the Piazza, with its shuffling hoards just

happy to be there, to say they've been to Venice, and with little

experienced beyond the café bands, the buzz and the pigeons. Which neatly

loops us back to the start of this review.

The photo below (from the book above) shows the Doge's

Palace in 1915, with brick supports under the arches and protective

scaffolding around the sculpture of Adam & Eve on the corner in case of

bombing.

|

|

|

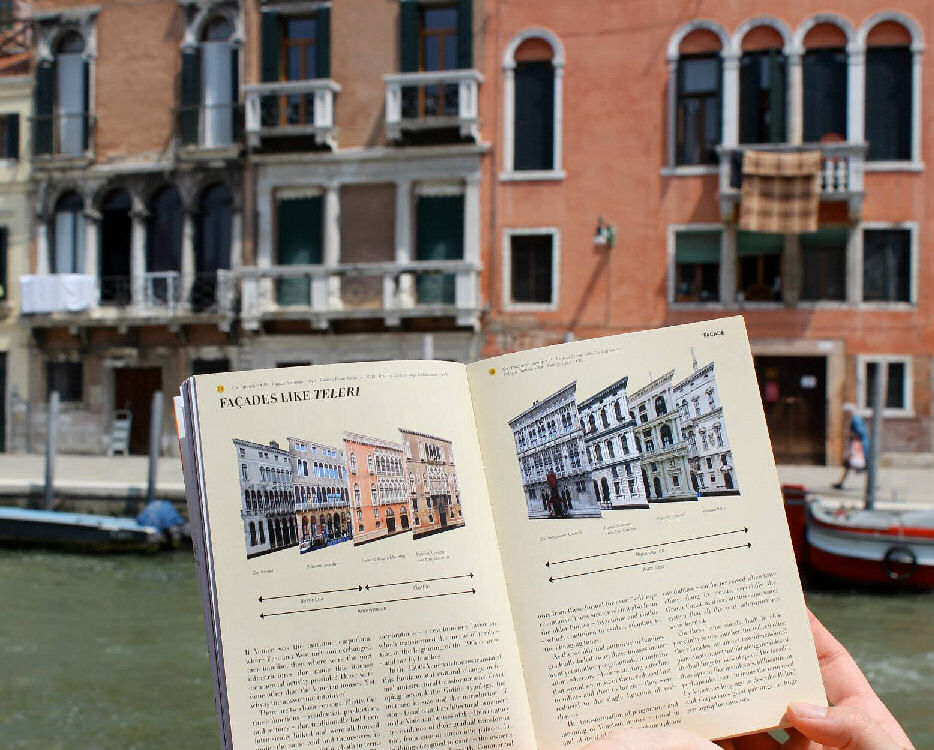

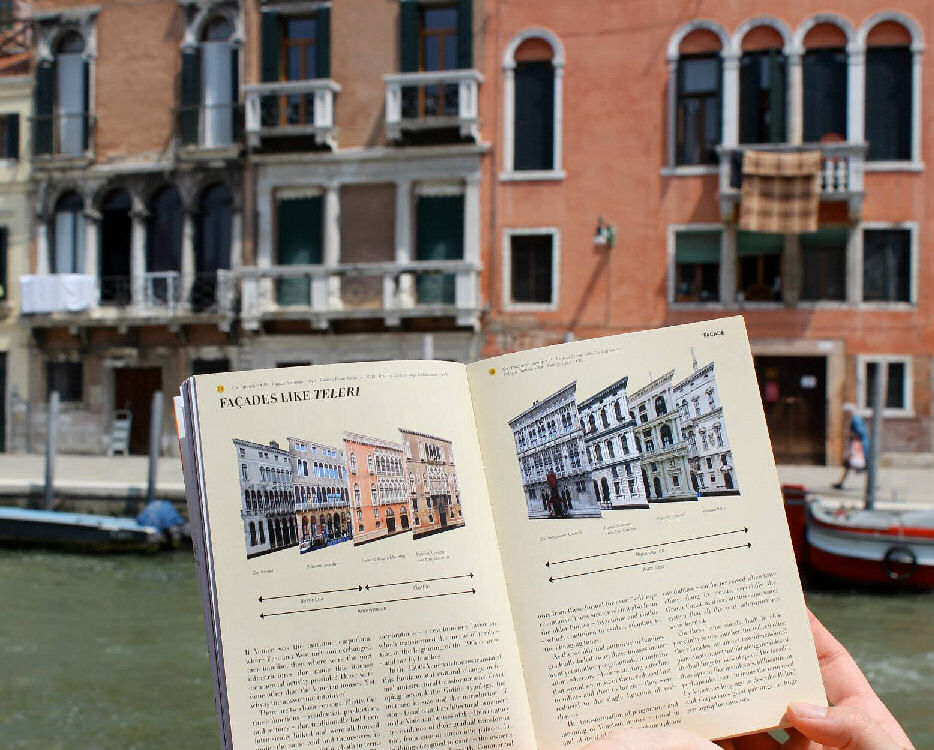

Giulia Foscari Elements of Venice

If I tell you that this book was written to accompany

Elements of Architecture, an exhibition developed as part of the 2014

Venice Architecture Biennale you, like me, might expect an insubstantial and

hastily-created book heavy on concept and light on content. How wrong we'd

both be. Firstly I need to warn you that to pick up this paperback is to

have to have it. It's a gorgeous little brick of a book, full of photos,

plans, charts, graphs, drawings and isometric views to excite us fans of

architecture and cityscapes. Each of

the book's chapters concentrates on an element of

Venice's architectural fabric. The one devoted to façades is a bit of a

catch-all but later ones about, for example, staircases and fireplaces

are fascinatingly confined. It seems that the book was created in

haste to catch the exhibition, but you wouldn't know it - there is much

knowledge being imparted and many fresh facts to pick up. There are pages

devoted to why, and how, the churches are orientated the way they are, and

to Napoleon's impact on the fabric of the city. There's a list of Venice's

major destructive fires down the centuries and an analysis of the ways, and

directions, in which Venetian houses were added to. The damages wrought by

tourism crop up unsurprisingly often. destructive fires down the centuries and an analysis of the ways, and

directions, in which Venetian houses were added to. The damages wrought by

tourism crop up unsurprisingly often.

The language can descend into arcane

architectural-theoretical gobbledygook, but it does this surprisingly

rarely, and more in the accompanying quotes than in the text. I hope that

I'm giving you an impression of a desirable thing to grace your bedside

table, for picking up when you need a fix of what you love looking at in

Venice, with the good chance you'll learn something too, or at least get a

different slant on something you may have taken for granted.

Robert L France

Veniceland Atlantis

The bleak future of the World's

favourite city

To attempt a comprehensive and comprehensible

review of the social and environmental catastrophes facing

Venice would be enough of a challenge, one would think. To do so

whilst also weaving the city's cultural and fictional fabric

through the facts and figures would seem to be both admirably

and foolishly ambitious. But in this book Robert France pulls

this off, and elegantly with it. The facts and futures are

presented in a winningly understandable and untechnical way,

guaranteed to enlighten and depress in equal measure. Things

really aren't looking good for Venice, and the way that this

fact plays up to the city's image as a place of post-hubris

decline and slow death is covered here too. The book manages to

be true to

the facts and the spirit of Venice, is what I'm trying to say. Being an optimistic sort of guy I tend to try to

block out a lot of the issues dealt with in this book, but to do

so is to live in a fantasy world, which is also somewhat

appropriate. (As the creator of this site I stand accused of

this and confess freely.) The scary facts are presented in a

serious, but not despairing way. Rising water levels, erosion

caused by speeding boats, pollution, pigeons, overvisiting,

governmental apathy and lassitude - this is stuff all serious

Venetophiles need to know about and this book is a one-stop

source for getting up to speed on the problems and possible

solutions. Some of the facts, especially in the section on the

tourist hoards forcing out the locals, will make most jaws drop.

Three quarters of all visitors are day-trippers, the tourism

levels (proportion of tourists to residents) are nine times

higher than Florence, the cruise ships can contain the

equivalent of fifty tour buses each and bring ten percent of all

tourist revenue. And most amazingly - sixty percent of all

cruise ship passengers don't get off the boat! Another

weird one: tourists are responsible for thirty-five percent of

all economic activity, but make eighty-three percent of the

waste. There

was once a website too which, amongst other things,

had colour versions of the black and white photos in the book,

but it seems to be no more. I

don't know if the decision to go with monochrome in the book was

made freely or forced by financial considerations but it doesn't

detract and chimes well with the book's serious,

non-coffee-table, nature. A new necessary purchase for all good

Venice bookshelves.

Martin Gayford

Venice: City of Pictures

Reading the title you're entitled to wonder if

his is a book of pictures painted in Venice or pictures painted

of Venice. And the answer is it's both - Venetians up to Tiepolo

and visitors from then on. It tells stories you may have read

before but mixes them up appealingly. So the often-told tale of

Bellini meeting Durer, as reported in the latter's letters,

is mixed in with both their dealings with Isabella D'Este and

Giorgione's life and fresco decoration of the Fondaco dei

Tedeschi. The author is famous for his books about David Hockney,

who gets more than his fair share of gratuitous mentions as this

book begins. But then we settle in to the Bellini family,

Titian, Tintoretto, Veronese's trials over his Last Super,

Tintoretto and his daughter - the classic story with

fashionable additions. It's an easy read with just enough

detours from the usual and fresh focuses to keep us veterans

interested.

|

|

Marie-Jose Gransard

Venice: A Literary Guide for Travellers

Literary Companions to Venice - books of

collections of writings from the big and famous names - are not rare, but this isn't quite one of those. Under various

nebulous chapter headings - 'Faith Art and Politics', 'Lust and Love', 'Death and Mystery' - the author details the reactions of visitors to

Venice. and the rhapsodies of some locals. All the usuals get their

stories aired - Henry James, the Ruskins, Byron, Casanova, d'Annunzio, for

examples - plus a few less common names, like Turgenev, Chekhov and Oscar

Wilde. Authors who've set stories in Venice get dealt

with too, and film-makers too, in a book that doesn't plough a narrow furrow. It's all here, but

you might already know much of it, if you've been paying attention to this

site. Such swathes of people and works are covered, though, that you can't

help but make discoveries.

Vaughan Hart and Peter

Hicks Sansovino's Venice

Like

Sanudo's Diaries and

Coryate's Crudities

Francesco Sansovino's Guidebook to Venice of 1561 is a book more

read about than read. The author was the son of the famed Venetian

architect and sculptor Jacopo, who was still alive when the book

was published, so the guide provides a picture of Renaissance

Venice just as Jacopo's work around Piazza San Marco was

coming to fruition, and before the coming of Palladio. The book

takes the form of a conversation between a Venetian and

Foreigner, the former walking and talking the latter around the

city, discussing history and customs as well as topography and

art. This literary dialogue form was not unusual in itself, but

it was unprecedented for a guide book. The Foreigner is

basically a straight man reacting, saying complimentary things,

and egging on the Venetian. The introduction gives us

much background and deals much with Francesco's attitude to and

discussions of his father's architecture. This fresh building

work gets discussed much here, which is no surprise as Hart is

primarily an architectural historian - he wrote the books, as it were, on dark-baroque Brit

architectural icons John Vanbrugh and Nicholas Hawksmoor, and with Peter Hicks

he gave us Palladio's Rome. When the guidebook itself gets

going it establishes its eclecticism pretty soon by discussing

customs, costume and prostitution. The blurb says that the book can still

be used as a guidebook, but I'm not sure this would be

practical, as the subject arrangement is eccentric and there is

much hopping around geographically. There is an index of

sorts, at the beginning, and the profusion of illustrations

(mostly modern colour photographs) makes it quite easy to know where to

stop if you're flipping through looking, for example, for

churches. Reading through the pages about churches illustrates

the variable worth of the text - there are occasional quirky

details but mostly you are just told that a particular church,

for example, is 'greatly praised by people' or that some others

'render the city noble and beautiful'. But after the glib

comment 'there are many churches, and all of them highly

esteemed 342', if you consult note 342 at the

end of the book it tells you that for more information you

should go to

churchesofvenice.com. A fresh achievement - I've made it

into the realm of scholarly notes!

Birgit Haustedt

Rilke's Venice

I freely admit to coming to this book with a clean slate, as it were, with regard to Rilke. But as I

start reading I learn that he loved Venice and wrote many poems

about the place. The book consists of eleven walks through parts

of Venice that Rilke knew, loved, wrote about and stayed in. The

book's copious quoting from his writings nicely evokes Venice in

the early part of the 20th Century, a period in the city's

history not much written about. It's not greatly different from

the present day, but there are occasional surprises, like

Rilke's complaint about the eternally noisy children in Campo

San Vio - a place for peaceful contemplation and the consumption

of tasty pizza slices on most of my recent visits. This is not a

book for one-sitting cover-to-cover reading but I'm slowly

working through it for regular Venice fixes, which is a role it

suits. Taking it and using it as a guidebook is, I would

suggest, for real Rilke fans, but reading this could well make

you one. The translation (from the German) is elegant and reads

so well you wouldn't know. Add to this the handsome red cloth

cover, with well-chosen photograph, and you have a tasteful

treat for Venice buffs.

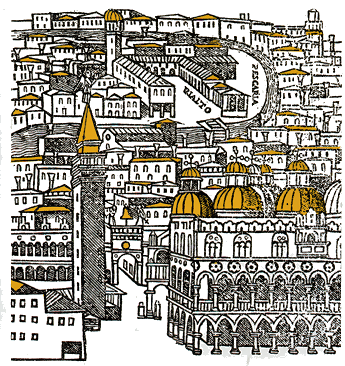

Deborah Howard and Henrietta McBurney

The Image of Venice: Fialetti's View and Sir Henry Wotton

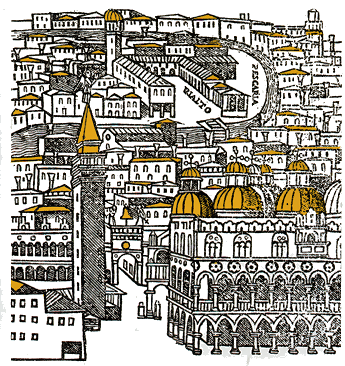

Oduardo Fialetti was an artist from Bologna who came, via

Rome and Padua, to Venice and worked with Tintoretto. These

influences led to his being an artist stronger on disegno

rather than the Venetian colorito and to his more

recent reputation resting on has many prints, rather than

his few paintings, several of which are to be found in Venice's churches. He also painted a

bird's-eye view of Venice which ended up, largely forgotten, at

Eton College, until it was restored a few years ago. This book

begins with essays telling the history of Venice and relating

this history to the production of maps and views, most famously

that of Jacopo de' Barbari, and how these views were produced to reflect and enhance the myth of Venice, and what they tell us of

the contemporary state of Venice's fortunes. They were not made to help you find your way

around. Other essays tell of the fact of the next 200 years of

maps all deriving from the de'Barbari view, the changes made on

the later maps, and the changes strangely not made. (The

now-demolished church of Santa Maria dell'Umiltà is shown

strangely large (see right) suggesting that the map may

have been made for a Jesuit, the church having been run by the

Jesuits before they were expelled in 1606.) In the absence of a

good recent book on maps of Venice this is all good stuff. There

are eleven essays in all, and in addition they deal in detail

with the restoration and tell of the Wotton, who was British

ambassador to Venice for many years and a provost of Eton, and

of the map's time in Eton.

reflect and enhance the myth of Venice, and what they tell us of

the contemporary state of Venice's fortunes. They were not made to help you find your way

around. Other essays tell of the fact of the next 200 years of

maps all deriving from the de'Barbari view, the changes made on

the later maps, and the changes strangely not made. (The

now-demolished church of Santa Maria dell'Umiltà is shown

strangely large (see right) suggesting that the map may

have been made for a Jesuit, the church having been run by the

Jesuits before they were expelled in 1606.) In the absence of a

good recent book on maps of Venice this is all good stuff. There

are eleven essays in all, and in addition they deal in detail

with the restoration and tell of the Wotton, who was British

ambassador to Venice for many years and a provost of Eton, and

of the map's time in Eton.

|

|

Lucy Hughes-Hallett

The Pike Gabriele d'Annunzio -

Poet, Seducer and preacher of War

Much was made in reviews and interviews with the author when

this biography was published of what a hard-to-love character d'Annunzio

is. He got through lovers like the rest of us get through toothbrushes, he

thought that nothing was more noble than (for other people, and lots of

them) to die for his country and irrigate its soil with a martryr's blood

and remains, and he pretty much prepared the ground - politically and

presentation-wise - for Mussolini to sell his fascism to a

well-prepared Italy, although he was far from a fan himself. Amongst some

other 'although's is the fact that most of his lovers had pretty impressive

personalities, and were mostly older and stronger than him. And he had a

style about him which, although far from making him lovable exactly, makes

his life prime material for a biographer who knows how balance and present.

That LH-H has a fine and sparkling prose style to match her subject makes

for an exceptionally fine read. D'Annunzio never lived anywhere very long,

mostly due to pursuing creditors, but he lived in Venice for

a good while, during most of WW1, in the Cassetta Rosa,

opposite what's now the Guggenheim Museum. There's a fair amount of Venetian

content here, then, including the fact that Hitler and Mussolini first met

in Venice in 1934, and that Hitler was unsurprisingly less than impressed

with the 'degenerate' content of that year's Biennale. D'Annunzio and his

then lover, the actress Eleanora Duse, were also regular strollers in the

Garden of Eden during its Edwardian prime, and the place featured in a

thinly-veiled novel he wrote about their relationship. The

unpaid bills that

his creditors were after him for were mostly for clothing, cleaning, cravats

and flowers. And the decadent plushness and high temperatures of his rooms

is a recurring theme, as is his sweet tooth. In summary - an unflinching but admirably

gripping biography of a man who's hard to admire. But you just might, a bit.

|

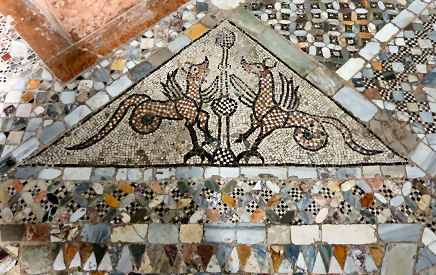

Thomas Jonglez and

Paola Zoffoli

Secret Venice

I don't tend to do guidebooks on these pages,

but this one is different. It actually lives up to the title,

even for one such as I who smugly thinks he's surprise proof,

what with making this site and almost a dozen visits. Some of

the secret places and a few weird facts were already known to

me, but I admit that lots weren't. The matching London volume I

was less enlightened by, showing that only by living in a city

can one truly know it. These guides push this point too, by

featuring the by-line Local guides by local people. The

presentation and page layouts are modern, with 'box outs' and

digression sections, but stylish and easy to read - not always

the case when designers try to be different. There are plaques

and carvings here I'd never noticed and buildings and gardens

that can be visited if you know who to ask (and the authors tell

you). Medical oddities, unknown libraries, eccentrics and

artists all feature. And who knew that Venice had two bowling

greens? You'd have to be a Venice resident of some age to not

get something from this book, I think, and I'm getting a lot.

Ian Kelly Casanova

With 2005's film and TV series, and not a few novels published

in recent years, you could hardly describe Casanova as a

forgotten figure. This is, however, the first big biography for

a while, and a more modern evaluation of the man is therefore

not a little overdue. Mr Kelly is no fusty academic, though, and

so this is likely to be seen as an entertainment rather than a

contribution to the scholarship, not that he doesn't do a pretty

thorough job. His main source is Casanova's own History of my

life (reviewed above) but he is at pains to sort the truth from

the myth-making by comparing the memoirs with known dates and

other written sources - he seems to have put in some time in the

Frari state archives. The emphasis is on Casanova as a performer

wherever he went - his theatrical childhood is seen here as the

major influence on his personality. Kelly being an actor himself

(and by some accounts a bit of a performer offstage too) makes

this emphasis understandable and not unconvincing. He gets a bit

carried away with his use of language sometimes, but when he

settles down this is a very readable romp. Kelly is also not

unsympathetic to Casanova's convincing contention that he was a

lover rather than a user of women. A lover-tally comparison

is made with the likes of Byron, and even Boswell, and Casanova

is found not to be the sex-machine that he's often painted.

|

|

Petr Kral

Loving Venice

This is another of those (usually) slim volumes that try to

define the essence of Venice with expressive flights and encompassing

theories. This one does at least balance the flights with some more grounded

observations of real life - real people and places do appear out of the

philosophic mists, as it were. It was written in 1998 so there are some

dated observations, like the mention of the only open cinema being the one

near the Accademia, for example, and talk of smoking indoors.

Grisaille is not a word one comes across often, but if you

had a pound for every time it's used in this book you'd soon have it's cost

covered. The author was once a Czech surrealist, we're told. Physically the

book is one of the usual lovely things published by Pushkin Press, with a

cover artily cropped from a Sickert. If a book can be said to be rarefied

then this one is, although to use my more usual confectionary-comparison

mode it's more of a soufflé than a bun, let alone a full meal, but the

flavour of Venice is strong.

Clemens F. Kusch & Anabel Gelhaar

Architectural Guide - Venice Buildings and Projects After 1950

Typical - you wait ages for a stylish guide to Venice's architecture from a

fresh and modern perspective and then two come along at once! But whereas

Elements of Venice by Giulia Foscari, reviewed above, takes a new view

of old buildings this one concentrates on more recent constructions. These

range from grand designs like the road bridge, Piazzale Roma, car park, Rio

Nova project to tasteful door cases. One of the two influential figures

presiding over this period is Eugenio Miozzi, a name new to me. His

influence as planning and building director for Venice stretches from 1931

(the Ponte della Libertà road bridge from the mainland was opened by

Mussolini in April 1933) and aside from the Piazzale Roma development just

mentioned included the Scalzi and Accademia bridges and some unrealised but

ambitious road-link projects. This book celebrates his ambition and the

talents of Carlo Scarpa but doesn't shy from some harsh observations and the

criticism of notable failures. The section on the Calatrava Bridge, for

example, is comprehensive to the point of incomprehensibility for the

non-specialist, but also points out the stupidity of the hurriedly added

wheelchair pod, which is badly designed, boils users' brains, and is never

working anyway. Offering free vaporetto trips between the station and the

bus station for wheelchair users would've been a much cheaper and more

elegant solution, as the text points out, admittedly in one of its less

elegantly-translated paragraphs. (The translation can best be described as

readable but eccentric.) The arguments for leaving Venice's fabric

well alone and preserved are aired too, along with the opposing view

revolving around the need to keep the city building-stock fresh and provide

accommodation for the non-mega-rich, thereby keeping the real people in

residence. In between are the adjustments and additions to existing

buildings which you often don't notice. The book is generally an aid to

pointing out the presence of buildings that you might pass by and ignore,

sometimes with good reason it must be confessed. The book is divided into eight colour-coded areas/walks, with maps,

and a ninth devoted to unrealised projects. This last chapter is a more

free-form discussion of famous unrealised projects like Frank Lloyd Wright's

palazzo and the radical hospital designed by Le Corbusier which was never

built, up past San Giobbe. There are lots of apartment blocks around

Venice's edges in here, and modern biennale pavilions. The modern building

we all remember, with a shudder, the bank (Cassa di Risparmio) in Campo

Manin, turns out to have been the work of one Angelo Scattolin, also

responsible for a couple of other sites for sore eyes in Venice. The entry

for the bank ends with the sentence, regarding the placing of a new building

so near the city centre, Not accidentally, it was an experiment

that was hardly to be repeated. So maybe we've that to be grateful for.

Venice's postwar architecture is a very rarely-covered

subject, which alone makes this book a somewhat essential purchase. Added to this is

it's sharp design and excellent photos, including many gorgeous clear aerial views

(see left) spread across two pages, making it another object of

desire. |

|

Mary Laven Virgins of Venice

This book was published in 2002, and one suspects that the

subsequent

fashion for novels that revolve around Venetian convent life has

been not-a-little inspired by its revelations. It's unflinching

in its detailing of transgressions and punishments and of the power of

economic and political considerations to ruin women's lives.

There's a good deal of friendship and support in evidence, but

the overriding impression is of women locked away - regardless

of their vocation, or lack of it - so as not to be a drain on

their family's financial resources. The convents also reflected

the stratification of the society outside their walls, with

cliques of idle women from the ruling families lording it over

the poor nuns forced into the convents by poverty, and forced to

work. There is a subtext that the convent life may have given

some women more chances to explore their talents and sexuality

than they would have had as wives or spinsters outside, but

incarceration is incarceration. This book sure adds

texture and detail to one's understanding of life behind the

walls, and the shifting nature of secular and religious

attitudes. It's a non-dry

must-read for anyone interested in the convents and the lot of

women in Renaissance Venice.

Mary Lutyens (editor)

Effie in Venice Mrs John Ruskin's letters home, 1849-52

The book opens with an indulgent but evocative,

and short, account of the editor's times in Venice, firstly in

1924 and then after the war in 1946 with her husband Joe Links,

and their later trips. She then gives us the background and

details the development of the relationship between John Ruskin

and Euphemia Gray. This period takes in the continued

non-consummation of their marriage, a situation which was

to continue in Venice. If you know anything about the couple it's

that their marriage failed due to this non-consummation, and

that an annulment was granted, at which point she was still a

virgin. There's been much salacious conjecture as to the reasons

for this. Ruskin himself writes, in a statement later, that

there were 'certain circumstances in her person which completely

checked' his passion. This has been interpreted as meaning many

things, from a repugnance at her pubic hair, which he wasn't

expecting having only ever seen female nude statues and

drawings, to a squeamishness at her menstruating. Far more

likely, given his observable and continued preference for

idealised young girls, he just couldn't take all the

real-life smells and textures of a real grownup woman, and all the

hygienic sacrifices that a physical relationship entails. The letters are

from Venice during the two trips, also taking in the

preparations and journeys. They're concerned mainly with Effie's

social whirl - the parties she goes to, the Austrian soldiers

she meets and the frocks she wears and admires. Equally there's

much about the Ruskin in-laws and their attitude towards her,

which was rarely what one would call supportive. So there's a lot

of reading between the lines to be done regarding the couple's

separate lives in Venice and how much the parents (Effie's also)

contributed to the divisive emotional stew. Without this back-story the

letters make somewhat tedious reading, and even with it I found

myself skipping whole chunks regarding the mixings and cupboard-skeletons of European royalty, and who's

saying what about whom. Some juicy Venetian details, to be sure,

but not enough to make this more than a cautious recommendation

for the general reader. Towards the end there's the excitement

of a robbery and Ruskin challenged to a duel. The book ends with

Effie writing to her mother about a sitting for Millais, the man

with whom she would finally lose her L-plates.

Judith Mackrell The Unfinished

Palazzo

This book recounts the lives of the three women

who stamped their identities upon the eternally-unfinished Palazzo Venier dei Leoni in the 20th century. Identity-stamping amounted

to the life's work of Marchesa Luisa Casati who rented the one-story ruin

to stage wild, gilded and gaudy parties. Her society could be so

described as well - Diaghilev, D'Annunzio, Fortuny

and Giovanni Boldini (who painted the famous portrait of her

right) all have their parts to play in her early

development, with the later lovers and friends so numerous and

famous as to make my revealing them amount to almost a plot

spoiler. Her time in Venice

allows the author to sidetrack into the lives of Venetians

Veronica Franco and Elena Cornaro Piscopia but this is a book

more about frocks and gossip than feminism. And the Marchesa spends

little of her life in Venice. I'd had my fill of her, and her

shallow and spectacular party-centric life, to be honest, quite

a few pages before we moved onto the shorter of the three life

stories. Doris, Viscountess Castlerosse starts life as a girl from Streatham

but using her looks, long legs and bedroom skills on a

succession of rich and titled men, works her way towards one who

might marry her. Her famous friends include Noel Coward, Winston

Churchill, Cecil Beaton and

Beverly Nichols. In a world where women sometimes have to become

prostitutes just to survive the fact that Doris does it for fur

coats and fripperies does little to make you warm to her. (The

UK tabloids have recently got into a froth about her all over

again as she's the actor Cara Delavigne's great aunt.) She eventually

needs to leave London, lest her relationship with Winston

Churchill become better known and hinder his rise, and so she

sails to New York, and there comes over all lesbian. This is

when she acquires The Palazzo Venier, using said lover's money.

(The author never uses the word 'lesbian' for some reason,

always calling such relationships 'Sapphic'.) But Doris just

gets to throw one end-of-season party there before the impending

war means she must leave, never to return. So with maybe a few

weeks spent in Venice in all the years covered by the book so

far, we embark on the second half of the book anticipating that

we and Peggy Guggenheim might now spend more time there, and

maybe concern ourselves with more than parties and sex. But after a brief Venetian frisson as Peggy makes an early

visit and becomes enamoured it's down to the usual round of

dysfunctional relationships, tragic parenting, much sex and much too little

humanity. She acquires the larger part of her collection of

modern art in Paris just before the Nazis march in, so getting

them all for knock-down prices from fleeing dealers and artists.

Her concern for getting these works out before the Nazis arrive

took priority over the more humanitarian concerns that others

laboured for. There is an attempt to make us forgive the woman's

entitled and self-centred insensitivity by blaming it on

insecurity and self-doubt, but I wasn't convinced. Peggy

Guggenheim's declining years at least keep us in Venice for a